[Content Warnings can be found here]

Hello again, my dear friend! A merry November to you. How have you been of late? Please savor the first segment of my next tale, with included illustrations once again!

Out of Paradise

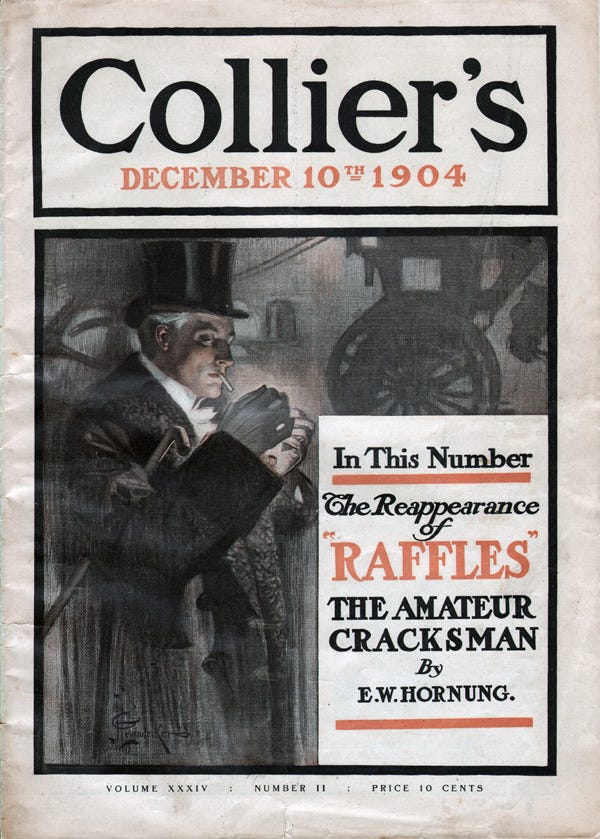

Illustration by J. C. Leyendecker. Image description in caption.

If I must tell more tales of Raffles, I can but back to our earliest days together, and fill in the blanks left by discretion in existing annals. In so doing I may indeed fill some small part of an infinitely greater blank, across which you may conceive me to have stretched my canvas for the first frank portrait of my friend. The whole truth cannot harm him now. I shall paint in every wart. Raffles was a villain, when all is written; it is no service to his memory to glaze the fact; yet I have done so myself before to-day. I have omitted whole heinous episodes. I have dwelt unduly on the redeeming side. And this I may do again, blinded even as I write by the gallant glamour that made my villain more to me than any hero. But at least there shall be no more reservations, and as an earnest I shall make no further secret of the greatest wrong that even Raffles ever did me.

I pick my words with care and pain, loyal as I still would be to my friend, and yet remembering as I must those Ides of March when he led me blindfold into temptation and crime. That was an ugly office, if you will. It was a moral bagatelle to the treacherous trick he was to play me a few weeks later. The second offence, on the other hand, was to prove the less serious of the two against society, and might in itself have been published to the world years ago. There have been private reasons for my reticence. The affair was not only too intimately mine, and too discreditable to Raffles. One other was involved in it, one dearer to me than Raffles himself, one whose name shall not even now be sullied by association with ours.

Suffice it that I had been engaged to her before that mad March deed. True, her people called it "an understanding," and frowned even upon that, as well they might. But their authority was not direct; we bowed to it as an act of politic grace; between us, all was well but my unworthiness. That may be gauged when I confess that this was how the matter stood on the night I gave a worthless check for my losses at baccarat, and afterward turned to Raffles in my need. Even after that I saw her sometimes. But I let her guess that there was more upon my soul than she must ever share, and at last I had written to end it all. I remember that week so well! It was the close of such a May as we had never had since, and I was too miserable even to follow the heavy scoring in the papers. Raffles was the only man who could get a wicket up at Lord's, and I never once went to see him play. Against Yorkshire, however, he helped himself to a hundred runs as well; and that brought Raffles round to me, on his way home to the Albany.

"We must dine and celebrate the rare event," said he. "A century takes it out of one at my time of life; and you, Bunny, you look quite as much in need of your end of a worthy bottle. Suppose we make it the Café Royal, and eight sharp? I'll be there first to fix up the table and the wine."

And at the Café Royal I incontinently told him of the trouble I was in. It was the first he had ever heard of my affair, and I told him all, though not before our bottle had been succeeded by a pint of the same exemplary brand. Raffles heard me out with grave attention. His sympathy was the more grateful for the tactful brevity with which it was indicated rather than expressed. He only wished that I had told him of this complication in the beginning; as I had not, he agreed with me that the only course was a candid and complete renunciation. It was not as though my divinity had a penny of her own, or I could earn an honest one. I had explained to Raffles that she was an orphan, who spent most of her time with an aristocratic aunt in the country, and the remainder under the repressive roof of a pompous politician in Palace Gardens. The aunt had, I believed, still a sneaking softness for me, but her illustrious brother had set his face against me from the first.

"Hector Carruthers!" murmured Raffles, repeating the detested name with his clear, cold eye on mine. "I suppose you haven't seen much of him?"

"Not a thing for ages," I replied. "I was at the house two or three days last year, but they've neither asked me since nor been at home to me when I've called. The old beast seems a judge of men."

And I laughed bitterly in my glass.

"Nice house?" said Raffles, glancing at himself in his silver cigarette-case.

"Top shelf," said I. "You know the houses in Palace Gardens, don't you?"

"Not so well as I should like to know them, Bunny."

"Well, it's about the most palatial of the lot. The old ruffian is as rich as Crœsus. It's a country-place in town."

"What about the window-fastenings?" asked Raffles casually.

I recoiled from the open cigarette-case that he proffered as he spoke. Our eyes met; and in his there was that starry twinkle of mirth and mischief, that sunny beam of audacious devilment, which had been my undoing two months before, which was to undo me as often as he chose until the chapter's end. Yet for once I withstood its glamour; for once I turned aside that luminous glance with front of steel. There was no need for Raffles to voice his plans. I read them all between the strong lines of his smiling, eager face. And I pushed back my chair in the equal eagerness of my own resolve.

"Not if I know it!" said I. "A house I've dined in—a house I've seen her in—a house where she stays by the month together! Don't put it into words, Raffles, or I'll get up and go."

"You mustn't do that before the coffee and liqueur," said Raffles laughing. "Have a small Sullivan first: it's the royal road to a cigar. And now let me observe that your scruples would do you honor if old Carruthers still lived in the house in question."

"Do you mean to say he doesn't?"

Raffles struck a match, and handed it first to me. "I mean to say, my dear Bunny, that Palace Gardens knows the very name no more. You began by telling me you had heard nothing of these people all this year. That's quite enough to account for our little misunderstanding. I was thinking of the house, and you were thinking of the people in the house."

"But who are they, Raffles? Who has taken the house, if old Carruthers has moved, and how do you know that it is still worth a visit?"

"In answer to your first question—Lord Lochmaben," replied Raffles, blowing bracelets of smoke toward the ceiling. "You look as though you had never heard of him; but as the cricket and racing are the only part of your paper that you condescend to read, you can't be expected to keep track of all the peers created in your time. Your other question is not worth answering. How do you suppose that I know these things? It's my business to get to know them, and that's all there is to it. As a matter of fact, Lady Lochmaben has just as good diamonds as Mrs. Carruthers ever had; and the chances are that she keeps them where Mrs. Carruthers kept hers, if you could enlighten me on that point."

As it happened, I could, since I knew from his niece that it was one on which Mr. Carruthers had been a faddist in his time. He had made quite a study of the cracksman's craft, in a resolve to circumvent it with his own. I remembered myself how the ground-floor windows were elaborately bolted and shuttered, and how the doors of all the rooms opening upon the square inner hall were fitted with extra Yale locks, at an unlikely height, not to be discovered by one within the room. It had been the butler's business to turn and to collect all these keys before retiring for the night. But the key of the safe in the study was supposed to be in the jealous keeping of the master of the house himself. That safe was in its turn so ingeniously hidden that I never should have found it for myself. I well remember how one who showed it to me (in the innocence of her heart) laughed as she assured me that even her little trinkets were solemnly locked up in it every night. It had been let into the wall behind one end of the book-case, expressly to preserve the barbaric splendor of Mrs. Carruthers; without a doubt these Lochmabens would use it for the same purpose; and in the altered circumstances I had no hesitation in giving Raffles all the information he desired. I even drew him a rough plan of the ground-floor on the back of my menu-card.

"It was rather clever of you to notice the kind of locks on the inner doors," he remarked as he put it in his pocket. "I suppose you don't remember if it was a Yale on the front door as well?"

"It was not," I was able to answer quite promptly. "I happen to know because I once had the key when—when we went to a theatre together."

"Thank you, old chap," said Raffles sympathetically. "That's all I shall want from you, Bunny, my boy. There's no night like to-night!"

It was one of his sayings when bent upon his worst. I looked at him aghast. Our cigars were just in blast, yet already he was signalling for his bill. It was impossible to remonstrate with him until we were both outside in the street.

"I'm coming with you," said I, running my arm through his.

"Nonsense, Bunny!"

"Why is it nonsense? I know every inch of the ground, and since the house has changed hands I have no compunction. Besides, 'I have been there' in the other sense as well: once a thief, you know! In for a penny, in for a pound!"

It was ever my mood when the blood was up. But my old friend failed to appreciate the characteristic as he usually did. We crossed Regent Street in silence. I had to catch his sleeve to keep a hand in his inhospitable arm.

"I really think you had better stay away," said Raffles as we reached the other curb. "I've no use for you this time."

"Yet I thought I had been so useful up to now?"

"That may be, Bunny, but I tell you frankly I don't want you to-night."

"Yet I know the ground and you don't! I tell you what," said I: "I'll come just to show you the ropes, and I won't take a pennyweight of the swag."

Such was the teasing fashion in which he invariably prevailed upon me; it was delightful to note how it caused him to yield in his turn. But Raffles had the grace to give in with a laugh, whereas I too often lost my temper with my point.

"You little rabbit!" he chuckled. "You shall have your share, whether you come or not; but, seriously, don't you think you might remember the girl?"

"What's the use?" I groaned. "You agree there is nothing for it but to give her up. I am glad to say that for myself before I asked you, and wrote to tell her so on Sunday. Now it's Wednesday, and she hasn't answered by line or sign. It's waiting for one word from her that's driving me mad."

"Perhaps you wrote to Palace Gardens?"

"No, I sent it to the country. There's been time for an answer, wherever she may be."

We had reached the Albany, and halted with one accord at the Piccadilly portico, red cigar to red cigar.

"You wouldn't like to go and see if the answer's in your rooms?" he asked.

"No. What's the good? Where's the point in giving her up if I'm going to straighten out when it's too late? It is too late, I have given her up, and I am coming with you!"

The hand that bowled the most puzzling ball in England (once it found its length) descended on my shoulder with surprising promptitude.

"Very well, Bunny! That's finished; but your blood be on your own pate if evil comes of it. Meanwhile we can't do better than turn in here till you have finished your cigar as it deserves, and topped up with such a cup of tea as you must learn to like if you hope to get on in your new profession. And when the hours are small enough, Bunny, my boy, I don't mind admitting I shall be very glad to have you with me."

I have a vivid memory of the interim in his rooms. I think it must have been the first and last of its kind that I was called upon to sustain with so much knowledge of what lay before me. I passed the time with one restless eye upon the clock, and the other on the Tantalus which Raffles ruthlessly declined to unlock. He admitted that it was like waiting with one's pads on; and in my slender experience of the game of which he was a world's master, that was an ordeal not to be endured without a general quaking of the inner man. I was, on the other hand, all right when I got to the metaphorical wicket; and half the surprises that Raffles sprung on me were doubtless due to his early recognition of the fact.

On this occasion I fell swiftly and hopelessly out of love with the prospect I had so gratuitously embraced. It was not only my repugnance to enter that house in that way, which grew upon my better judgment as the artificial enthusiasm of the evening evaporated from my veins. Strong as that repugnance became, I had an even stronger feeling that we were embarking on an important enterprise far too much upon the spur of the moment. The latter qualm I had the temerity to confess to Raffles; nor have I often loved him more than when he freely admitted it to be the most natural feeling in the world. He assured me, however, that he had had my Lady Lochmaben and her jewels in his mind for several months; he had sat behind them at first nights; and long ago determined what to take or to reject; in fine, he had only been waiting for those topographical details which it had been my chance privilege to supply. I now learned that he had numerous houses in a similar state upon his list; something or other was wanting in each case in order to complete his plans. In that of the Bond Street jeweller it was a trusty accomplice; in the present instance, a more intimate knowledge of the house. And lastly, this was a Wednesday night, when the tired legislator gets early to his bed.

How I wish I could make the whole world see and hear him, and smell the smoke of his beloved Sullivan, as he took me into these, the secrets of his infamous trade! Neither look nor language would betray the infamy. As a mere talker, I shall never listen to the like of Raffles on this side of the sod; and his talk was seldom garnished by an oath, never in my remembrance by the unclean word. Then he looked like a man who had dressed to dine out, not like one who had long since dined; for his curly hair, though longer that another's, was never untidy in its length; and these were the days when it was still as black as ink. Nor were there many lines as yet upon the smooth and mobile face; and its frame was still that dear den of disorder and good taste, with the carved book-case, the dresser and chests of still older oak, and the Wattses and Rossettis hung anyhow on the walls.

It must have been one o'clock before we drove in a hansom as far as Kensington Church, instead of getting down at the gates of our private road to ruin. Constitutionally shy of the direct approach, Raffles was further deterred by a ball in full swing at the Empress Rooms, whence potential witnesses were pouring between dances into the cool deserted street. Instead he led me a little way up Church Street, and so through the narrow passage into Palace Gardens. He knew the house as well as I did. We made our first survey from the other side of the road. And the house was not quite in darkness; there was a dim light over the door, a brighter one in the stables, which stood still farther back from the road.

"That's a bit of a bore," said Raffles. "The ladies have been out somewhere—trust them to spoil the show! They would get to bed before the stable folk, but insomnia is the curse of their sex and our profession. Somebody's not home yet; that will be the son of the house; but he's a beauty, who may not come home at all."

"Another Alick Carruthers," I murmured, recalling the one I liked least of all the household, as I remembered it.

"They might be brothers," rejoined Raffles, who knew all the loose fish about town. "Well, I'm not sure that I shall want you after all, Bunny."

"Why not?"

"If the front door's only on the latch, and you're right about the lock, I shall walk in as though I were the son of the house myself."

And he jingled the skeleton bunch that he carried on a chain as honest men carry their latchkeys.

"You forget the inner doors and the safe."

"True. You might be useful to me there. But I still don't like leading you in where it isn't absolutely necessary, Bunny."

"Then let me lead you, I answered, and forthwith marched across the broad, secluded road, with the great houses standing back on either side in their ample gardens, as though the one opposite belonged to me. I thought Raffles had stayed behind, for I never heard him at my heels, yet there he was when I turned round at the gate.

"I must teach you the step," he whispered, shaking his head. "You shouldn't use your heel at all. Here's a grass border for you: walk it as you would the plank! Gravel makes a noise, and flower-beds tell a tale. Wait—I must carry you across this."

It was the sweep of the drive, and in the dim light from above the door, the soft gravel, ploughed into ridges by the night's wheels, threatened an alarm at every step. Yet Raffles, with me in his arms, crossed the zone of peril softly as the pard.

It has uplifted me to write to you again; anticipate my next letter shortly, my good friend.

With excitement,

Bunny Manders